Eau Pernice’s sculptures circle both the imaginary and the material. On the one hand, her work relies on a hand-made and artisanal quality, whereas, on the other, the mysterious and hidden. Physical touch transforms basic, often singular, rudimentary materials into complex structures that carry a myriad of associations. Simple gestures and processes are utilised to highlight the potential of the material – its sense of power and autonomy – and how this might become active, serving as the main instrument within artistic fabrication. By refraining from the use of technology or a multitude of tools (simple devices such as a hammer and sewing machine are used), the artist focuses on how her own hands and physical capabilities might directly shape the visual outcome of the artwork. This approach to making creates both a tactile and psychological link between the maker and the final fabricated object, possibly deepening the viewer’s understanding of the artwork as an artefact. Pernice’s personal investment in this temporal aspect of making adds further significance to her work, which is itself concerned with key themes such as rhythm, melody, passage, nonsense, disorder, voice, consumption, media, communication, and storytelling. Most notably, these ideas are explored in her backwards-singing performances.

For example, after a recent residency at PADA studios in Barreiro, Portugal, in May and June 2023, the artist interlocks segments of bamboo into shapes reminiscent of music stands. First, Pernice gathered bamboo sticks from beaches beside the river Tagus, bringing these back to the studio and painting the long, limb-like branches with silver school paint. By using found wood spotted within the dunes and washed up on the sand, as opposed to buying industrially produced timber or metal rod, characterised by its standardised linear shape, the sculptures are consequently site-specific, fundamentally tied to the location in which they are produced and the characteristic features of the surrounding landscape. The immediate vicinity of this collective studio can indeed be described as an abandoned and industrial space, positioned just outside the ferry-port of Lisbon, fallen into a state of disrepair, waste and disuse. Pernice relies upon the innate properties of the bamboo – its lightness and hollow interior – to create her form, fitting individual pieces, cut with a saw, together. No music stand looks the same. Some lean to the side, buckling or drooping, whilst others stand defiantly off the floor, dominating the space with their pronged, outstretched feet. The slight bend of the bamboo creates a comical effect: one can imagine these works buffeted by the wind like river reeds, or possibly waving, bopping in time to the music in the manner of a choir or band.

2023, bamboo and tempera

2023, bamboo and tempera

Although the surface of these constructions playfully imitates the sheen of heavy metal used in music stands by professional orchestral musicians to keep their sheet music solidly in place, they are in fact ephemeral, impractical, oversized, and unfit for purpose. Moreover, considering how Pernice’s practice is influenced by an inquisitive and ludic approach to language, singing, and composition, the naming of these works is undeniably important. The title ‘Dynamics in A Choir (After two members went off to pursue a duo career the internal hierarchy was in question)’ certainly plays on the idea that the sculptural music stands in fact represent the persona of missing musicians or performers. The verb and noun ‘stand’ itself indicate the anthropomorphic nature of the music stand, which arguably serves as an extension of the body, carrying or holding the music for a player to follow, affirming their place, and guiding them through time and space. In this sense, the item of the music stand carries a strong degree of agency – serving as the conduit between the musician and music they produce, displaying the score or script which facilitates a harmonious performance taking place. Pernice’s use of grouping, placing her free-standing sculptures together in different positions and numbers, further highlights how these works might function performatively in a gallery space. In this image, for example, there is a suggestion that a meaningful dynamic or conversation exists between the sculptures themselves, perhaps happening off stage, to which the viewer is not privy to, and can only guess at [see Fig. 1]. The title implies that these hollow bamboo sculptures are self-sufficient – capable of producing their own sound and music, without need for an audience to listen, or a viewer to see. The artist thus asks us to suspend our imagination, and to consider whether a music stand might stand in for a musician.

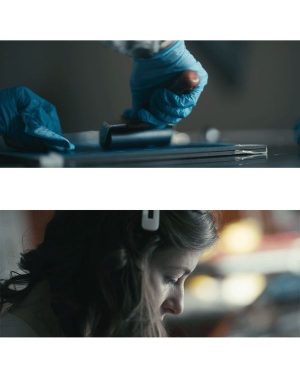

As these floor-based sculptures encourage the viewer to probe more deeply into how we might ascertain the presence of either sound and silence, including the idea that music need not necessarily be played to exist, Pernice’s wall-based sculptures produced at PADA studios respond more closely to the visual: symbols, signage, and notation. For instance, in ‘Untitled‘ a length of black ribbon curls and folds in upon itself, pinned and fastened together with lightly sewn thread. This structuring of the continuous and supple line of the ribbon into the format of a mesh grid, draping softly down from the white gallery wall, creates a soft play of shadows and tones [see Fig. 2].

Figure 2: Untitled, ribbon and thread, dimensions variable, 2023

The salient black form against the contrasting white ground is certainly comparable with formal appearance of musical scores. The viewer might consider how sound is coded and processed visually: imagining perhaps the presence of criss-cross ink upon paper, indicating staves, notes, keys, and time, or perhaps even a labyrinth-like graph, maze, map, architectural or mathematical drawing. ‘Honeycomb for the Moon’ is immediately recognisable, however, as the sickle-shape of a crescent moon [see Fig. 3].

Figure 3: Honeycomb for the Moon, ribbon and thread, dimensions variable, 2023.

In this sense, the black of the ribbon carries association with velvety night, hinting to a world of darkness, magic, and ritual. As Pernice explains in a brief commentary accompanying the soft textile works made during her residency, she was heavily influenced by a trip to Porto to visit the assumed inspiration for the bookshop in J.K Rowling’s Harry Potter. If one considers this context of production, the ribbon-pieces perhaps take on associations of runes, witches and wizards’ cloaks, or the draping robes of dementors – monstrous characters who live in the dark in Rowling’s fantasy world. Moreover, ‘honeycomb’ itself refers to a device used within lighting, stage design, and film. This hexagonal mesh traps peripheral light and reduces glare, enabling photographers and camerawomen to capture their subjects under the illusion of darkness or seemingly naturalistic conditions. The sculptures are therefore closely tied to representations of light and dark, as well as day and night, nature and artifice, fantasy and reality. It is primarily the use of colour, form and material, which embeds these artworks so strongly in the terrain of music and literature: pages of a fantasy book or the invisible sound of a music score.