Art Hub Newsletter #13, 2021

by Eau Pernice

(Translation by Dan Marmorstein) Jump to the original Danish version here

This year, the fall of the leaves has been especially prolonged, and I wanted to witness the moment when a leaf lets go of its branch and falls to the ground. It’s got something to do with catching sight of the dividing line between two seasons. I didn’t see the fall. So I don’t know exactly when it happened. And now it’s winter. “Wann?”, which means ‘when’ in German, is the English word, “Now!”, enunciated backwards.

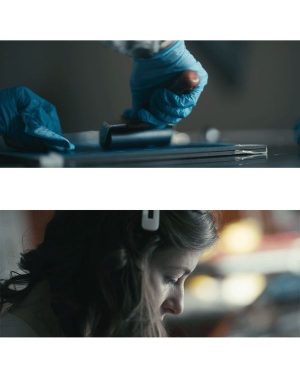

I often come across these pairs of words as I re-write well-known pop songs into backwards songs: ‘Leave’ (and, for that matter, ‘leaf’) are ‘feel’ spoken backwards. ‘Fall’ is ‘love’ spoken backwards. And vice versa. I wonder if it means something that these words can be found ensconced within one another: to love and to fall. To leave and to feel. This is an abstract thesis. In order to render it concrete, I got together with somebody who could tell me about the physical act of falling. Skjold Rambow is a stuntman and a student at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, and I’ve seen him falling in video pieces by Kåre Frang (As we speak, 2020 and Changes, 2020) and in Being Seen Seeing, 2022, by Majse Vilstrup. My guiding notion is that if I describe a fall backwards, I will gain a new understanding of what it is to love. I have recorded my conversation with Skjold Rambow as a sound file, transcribed it, and taking my point of departure in this, I’ve once again written the course of action backwards.

The stuntman is in his home. This is not a movie. Now it’s reality, because the stuntman is taking time off time off from his job. The stuntman looks at the abrasion on his leg. “No, no, it doesn’t hurt at all.” Eye contact with his girlfriend: she’s looking at the leg and looking back at him. “You’ve got to take care of yourself.” He rolls down the leg of his pants. Sequences of sentences – lines, thinks the stuntman, who’s about to head to work – are exchanged during slow inhalations. “I hurt myself when I was doing a stunt.” He takes up his bag from the floor and throws it over his shoulder, to which it clings, as if it were a prosthesis on the body that’s not moving. “Hi, I’m home!” he cries out, and backs out the door, closing it with his key sitting in the lock. He locks the door as he thrusts his two feet down into each of his shoes, with the other foot holding tightly onto the one shoe’s heel. Doesn’t he feel like loosening the shoelaces? The stuntman walks down the stairs, with his back facing the stairwell, at a rapid pace. He places the foot, confidently, on the next step without looking down. No, he looks upwards, in the direction opposite to the one he’s moving in. There’s an elastic movement in the foot, in the leg, as he lets his whole body fall to the next step, where the movement stiffens without any memory of the lightness in the fall he experienced just before. The stuntman is smiling as he closes the door to the stairwell in front of him.

Did he remember the order? Same choreography, in any event. His gaze is on the woman as he pulls the bicycle and himself away from her, in action. He doesn’t have to worry about the traffic that’s moving with him, behind. The bloodstains on the sidewalk are coagulating into droplets. They’re being absorbed up, through the air, to the handlebars and are crawling in between his fingers, as he loosens his hand’s grip on the bag, concealed in the hollow of his hand, which the blood now fills. He stops, lays the bike down on the ground, with the weight on the back wheel and the pedal, as the front wheel slowly starts to revolve. Then he glances at the woman passing by, as he gingerly allows himself to sink toward the ground: he places the free flat of his hand against the hard underlying layer, placing the weight on his other forearm, and lets the same shoulder sink down toward the cement surface, softly. He lies on his back, with his face turned away from the camera. Outside the picture’s cropping, he grabs hold of another bag, an empty one. The bag is in the hand, which he reaches toward the bloody face and he wipes away the blood. With the hand’s sweeping movements, the blood implodes inside the crushed bag that closes up its holes, as he loosens his hand’s pressure around it and rounds the back of his hand. He somersaults on the outermost part of the one shoulder. The legs are being thrown up in the air and he shoves off on the one forearm. Simultaneously with the legs pulling the lower body and then the upper body up, the bicycle twitches across the sidewalk, until, in one powerful jerk, it stands lopsidedly upright between his legs. He plunks himself down, forcefully, on the saddle. His feet tread backwards on the pedals, but the bicycle does not brake: it’s rolling back. The front wheel turns away from the curb, out towards the lane, and he cycles in a fast and wobbly way, with several bags on his back. His hair is sucking the wind and so as not to hold onto the handlebars too tightly – because each of his hands is concealing a bag with stage blood – he’s got to remind himself about this. Messing around with the two bags suspended over his shoulders might serve to render the accident more realistic. Okay, “What is it that makes me fall?”, thinks the stuntman. One invents when one is doing stunts. He’s waiting for a ‘go’. He lets his mind wander, cools off and relaxes the muscles in his body.

FALL ER LOVE BAGLÆNS

Art Hub Newsletter #13, 2021

af Eau Pernice

Løvfaldet i år var langstrakt, og jeg ønskede at se øjeblikket, hvor et blad slipper sin gren og falder mod jorden. Det handler om at se skellet mellem to sæsoner. Jeg så ikke faldet, jeg ved ikke, hvornår det præcis skete og nu er det vinter. ”Wann?”, som betyder ‘hvornår’ på tysk, er baglæns det engelske ”Now!”.

Disse ord støder jeg ofte på, når jeg omskriver kendte popsange til baglæns sange: ‘Leave’ (og ‘leaf’) er ‘feel’ baglæns. ‘Fall’ er ‘love’ baglæns. Og omvendt. Mon det har en betydning, at disse ord findes i hinanden: at elske og at falde. At forlade og at føle. Det er en abstrakt tese, og for at konkretisere det mødtes jeg med én, der kan fortælle mig om fysiske fald. Skjold Rambow er stuntmand og studerende ved det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi, og jeg har set ham falde i videoværker af Kåre Frang (As we speak, 2020 og Changes, 2020) og i Being Seen Seeing, 2022 af Majse Vilstrup. Min idé er, at hvis jeg beskriver et fald baglæns får jeg en ny forståelse af det at elske. Jeg har optaget min samtale med Skjold Rambow som lyd, transskriberet den, og med udgangspunkt deri har jeg genskrevet handlingsforløbet baglæns.

Stuntmanden er i sit hjem. Det er ikke en film, nu er det virkeligheden for stuntmanden har fri fra arbejde. Stuntmanden kigger på hudafskrabningen på sit ben. ”Nej, nej, det gør slet ikke ondt”. Øjenkontakt med hans kæreste, hun kigger på benet og tilbage på ham. ”Du skal passe på dig selv”. Han trækker buksebenet ned. En række sætninger – replikker, tænker stuntmanden, der lige om lidt går på arbejde – udveksles på langsomme indåndinger. ”Jeg slog mig, da jeg lavede et stunt”. Han trækker sin taske op fra gulvet og svinger den over skulderen, hvor den suger sig fast, som om den var en protese på kroppen, der ikke flytter sig. ”Hej!” råber han og bakker ud af døren, lukker den med sin nøgle siddende i låsen. Han låser, mens han stikker fødderne i hver sin sko, den anden fod holder fast på den ene skos hæl. Gider han at løsne snørebåndene? Stuntmanden går med ryggen ned ad trappen i et højt tempo. Han placerer foden fortroligt på næste trin uden at se ned. Han kigger opad, i modsat retning end den, han bevæger sig i. Der er en elastisk bevægelse i foden, i benet, når han lader hele kroppen falde til næste trin, hvor bevægelsen stivner uden et minde om letheden i faldet lige før. Stuntmanden smiler, da han lukker døren til opgangen foran sig.

Har han husket rækkefølgen? Samme koreografi i hvert fald. Hans blik er på kvinden, mens han trækker cyklen og sig selv væk fra hende, i gang. Han skal ikke bekymre sig om trafikken, den bevæger sig med ham, tilbage. Blodpletterne på fortovet trækker sig sammen til dråber. De suger sig op gennem luften til cykelstyret og kravler ind mellem hans fingre, idet han løsner håndens greb om posen, skjult i håndhulen, som blodet nu fylder. Han standser, lægger cyklen ned på jorden med vægten på baghjulet og pedalen, forhjulet begynder langsomt at dreje. Derefter kigger han mod den forbipasserende kvinde, mens han nænsomt lader sig selv synke mod jorden: han sætter den frie håndflade mod det hårde underlag, lægger vægten på den anden underarm og lader samme skulder synke ned til cementfladen, blidt. Han ligger på ryggen, med ansigtet drejet væk fra kameraet. Uden for billedets beskæring griber han om en anden, tom pose. Posen er i hånden, som han rækker mod det blodige ansigt og tørrer blodet væk. Med håndens fejende bevægelser imploderer blodet i den knuste pose, der idet han løsner sit håndtryk om den og runder håndryggen, lukker sine huller. Han ruller bagover på det yderste af den ene skulder. Benene kastes op i luften, og han sætter af på den ene underarm. Simultant med at benene trækker underkroppen og dernæst overkroppen op, spjætter cyklen over fortovet, til den i ét kraftigt ryk står skævt oprejst mellem benene på ham. Han sætter sig hårdt på sadlen. Fødderne træder bagud i pedalerne, men cyklen bremser ikke; den kører. Forhjulet drejer fra fortovskanten ud mod vejbanen, og han cykler hurtigt og slingrende med flere tasker på ryggen. Hans hår suger vinden og for ikke at tage for fast om styret, da hver hånd gemmer på en pose med teaterblod, må han minde sig selv om det. Det kunne gøre uheldet mere realistisk at han rodede med de to tasker, der hænger over hans skuldre. Okay, hvad gør, at jeg falder? tænker stuntmanden. Man opfinder, når man laver stunts. Han venter på et go. Han lader tankerne vandre, køler ned og løsner musklerne i kroppen.